Photographic Portraiture Requirements and Resources

As a class, photographic portraits differ from portrait paintings largely on the basis of verisimilitude. A direct physical link to the existence of the subject at the time of capture sets portrait photography apart from painting. Besides possessing more than just a flirtation with reality, there are many relationships and processes, some unique to photography, that can modify this bond. The power and the range of the modifications need to be examined in order to understand what it takes to capture the essence of a person in an image. As with most scientific inquiry throughout history, cataloging is the first step to understanding, and that will comprise an early endeavor here. Taken together, these manipulations constitute the art of photographic portraiture. In various advantageous combinations, they are what make great photographic portraits great. It is clear that many elements, from the noise structure of the film or sensor to an emotional backstory, contribute to an exceptional image. In the end, the dimensionality of the subject is delivered through a rich layering of all the contributions that come together in the presentation of the image. Physics, chemistry, physiology, psychology, sociology – each will be shown to have a role.

Because of the lifelike nature of what will increasingly become the domain of digital entities, the viewing of a photographic portrait evokes a natural two-way communication with the observer’s own knowledge providing an appreciable portion of the experience. Given the variation of this knowledge across individuals, it is likely that two observers perceive different, possibly appreciably different, versions of the same portrait. It will be of interest to explore how the apprehension of a portrait changes as the observer is supplied with more information. This information can be provided through increments in the basic physical properties of an image (e.g., resolution, tonality, signal-to-noise ratio). Alternatively, additional information can be packaged in more symbolic terms through such additions as cultural conventions or a detailed background narrative.

A similar hierarchy of interpretive influences is in play when viewing a medical image. The cognitive structure used to convey spatial detail undergoes an interpretation that is modified by the availability of exam notes and patient history. Going even further, it is of interest to determine how the impression of a patient ‘portrait’ changes over the longer term as the observer transitions from being a medical student to a resident to an attending and becomes an expert in possession of different, more complex representational structures. Such transformations are clearly evident in the physical domain as the range of cameras and photographic processes leave recognizable signatures on images for the trained observer, as do the tastes, techniques and skill of different photographers. Here again, analogous signposts can be discerned in diagnostic images leading the trained observer to a fuller understanding of the events, and limitations, surrounding the capture of the image. The two-way clinical communication can alter perceived patient status through the result of medical training and other relevant experience that bring to bear a range of preferences and biases on the processes of subjective appearance interpretation and clinical decision making.

These interactions and expectations will change for both aesthetic and clinical applications as photography evolves to incorporate new modes of digital representation such as high dynamic range imaging. The analysis of image viewing also can be extended to the somewhat less common form of portraiture, video, or even video with sound. There are also side branches of the portraiture family tree such as 3D stereograms, or their more modern equivalent, 3D CGI models. It will be of interest to investigate what each version has to contribute, and what each representation lacks. What can be established between the perceived quality of the portraits and the technical properties of these different image formats?

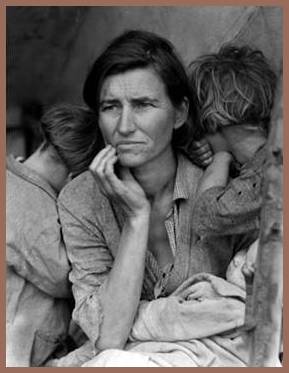

Clearly, one of the reasons the images presented above are icons of successful portraiture is that they are also archetypes of the human condition. What is it in those rectangles that make them so captivating? What in these particular examples induces the pathos? Is it the image composition, the physical photographic structure, the personal backstory, or possibly the sociopolitical context? To what extent can a given image by itself support the complex contributions of the higher forms of representation and to what extent are these concepts drawn from a system of common understanding and beliefs? What are the mechanisms that allow a meaningful history to alter or enhance image details into something more than luminance patterns, and what forms of representation convey immutable meanings that are innate to the objective structure of the photograph? These latter influences resulting from the physical properties of an image depend on more than the sensitivity of the human visual system and are perhaps more accessible through analytical models. Other physical properties have the capacity to extend beyond direct measurement. As an example, a common cultural association for Americans links color photography largely with the post-WWII period. In contrast, the dust bowl migrants maintain cultural associations with the B&W photographic era, although exceptions exist to both.

What other image parameters are required to support these compelling photographs? How do they differ across images? What would change if these physical properties were altered? Is anything to be learned about what physical informational capacities are possessed by Steve McCurry’s Kodachrome 35mm slide of the Afghan Girl and by Dorothea Lange’s gelatin silver print from the 4x5” nitrate negative of the Migrant Mother by teasing them apart on all their measurable dimensions? What would be captured by applying a diagnostic vector-magnitude measure of luminance and chromatic contrast to these images? Is organic image structure the same no matter what the venue? What if the higher associations were altered? What would change if these images had more upbeat stories attached? With time and analysis, some illuminating structure should emerge from the cataloging of these relations.

It might be possible to demonstrate the potency of some of these assertions with a few simple experiments. Consider what interactions occur between the physical and the cognitive. By changing the parameters that physically instantiate a given image, how do the aesthetic and emotive aspects get recast? What changes when the Migrant Mother image is colorized using the Kodachrome image characteristics of Afghan Girl? What happens when the Afghan Girl is viewed in B&W and those piercing green eyes turn grey?

Is it possible to relate the feelings these portraits induce back to the concepts of the Uncanny Valley? Images such as the two above are clearly at the acme of Mori’s scale. As images of what we know to be actual people, they easily draw out human feelings from our observation. What if the unease we feel with slightly imperfect representations is due to our inability to equivalently suspend disbelief for the less than totally accurate simulacra because there is nothing real to relate to? What if it is because we are not easily able to project the feelings we normally hold for flesh and blood human beings to a totally artificial situation, one counterfeit in both in context and in constitution? What changes in our perception might occur if a simulation wasn’t wrapped in a fiction, but instead, was presented in the context of a documentary? Could we come to accept the defects in the simulations in an environment based on reality as easily as we accept graininess in old film stock? Would the factual story compensate for the artificiality of the image and engage us in the same manner we are engaged by real actors performing in what we know to be a fiction in most movies. Perhaps combination of the fabricated representation and the fictitious story is currently too much for our perceptual acquiescence to evoke the higher level associations from within us as outlined above. Indeed, can the lessons learned from the examination of photographic portraiture be applied to the perceptual potholes in that last stretch of human likeness on Mori’s scale?

Familiarity/likeability/comfort level/rapport – these descriptors don’t begin to cover the richness of photographic portraiture. Just look at the iconic images above. The current descriptions of the Uncanny Valley are just a peek at a multidimensional perceptual surface. There must be better, more meaningful terms than familiarity. What is negative familiarity, strangeness? Polar terms such as beautiful and ugly are not always extensions of the same perceptual dimension and may contribute to the dimensionality of humanoid/human appearance in complex ways. Clearly, even a cursory look at the two faces above will begin to open up the richness of this domain. Mori himself implicitly argued for the existence of a multidimensional relation (motion / immobility v. familiarity / strangeness v. human likeness / dissimilarity). How many more distinct properties can be teased out by analyzing the representation of the human form in all its variations, especially through the examination of photographic portraiture’s best?

Even as Eastman Kodak is suffering the disruptive consequences of the transition to digital imaging, the George Eastman House is embracing the new technology in ways that enrich and preserve the older technology. In addition to new centers and institutes (see the links below), there is greater outreach to academic institutions across the arts, science and engineering. With what began as an effort to better serve their public by making a substantial portion of the museum’s collection available on the Internet (no small task when the issues of quality and capacity are so intimately involved), the George Eastman House is slowly becoming a institution representative of the entirety of photography. All this notwithstanding, the GEH needs to be even more involved with digital photography – both to properly represent the story of photography today, and tomorrow, as well as to use digital techniques to promote the entire collection of still images, movies and early photographic devices. It is important to bear in mind that while photography is more popular and accessible than ever, the majority of current photographers have never captured an image on film, nor are they likely to.

Brian C. Madden

Links:

University of Rochester / George Eastman House Collaborative Alliance

Eastman House Daguerreotype Project

The Image Permanence Institute, College of Imaging Arts & Sciences, RIT

George Eastman House International Museum of Photography & Film