Digital and me

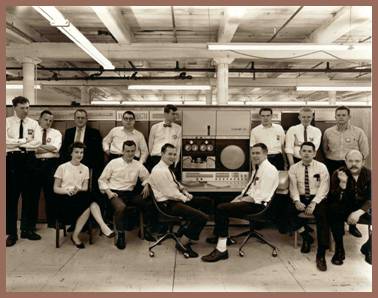

This photo gives a good idea of the look and feel of DEC in the ‘60s. Note the high mill ceilings (all soaked with lanolin, often necessitating plastic tarps in the summer to catch drips). There are 14 people in this picture, 13 are looking at the camera. The young Lincoln leaning on the DECtape drive and gazing out the window at the Assabet River is Russ Doane, who in a little over four years would hire me. He was a discrete component circuit designer when a data bus was a few twisted pairs and before the integrated circuit revolution sanitized design. At this time, about half the module schematics had his name on them – a goodly number of them in the PDP-6 they were standing around and had just constructed. To Russ’ right was Alan Kotok, architect of the future PDP-10 and later on to have so much to do with the development of the Web. To Alan’s right was Gordon Bell, the PDP-6 architect.

DNC

“Tell me, Brian, isn’t that a woman’s condition?”

Chief Engineer Dick Best at an Operations Committee meeting

The Direct Numerical Control system, although modular and reconfigurable, was much further along the OEM path toward being a complete end-product than most other Control Products Group offerings. In the DEC tradition, DNC demonstrated just how much could be done for relatively little expense. However, machine tool control design wasn’t a core DEC competency. There was a steep learning curve all around. Some of this progress can be seen by following the evolution of the test artifact machining quality.

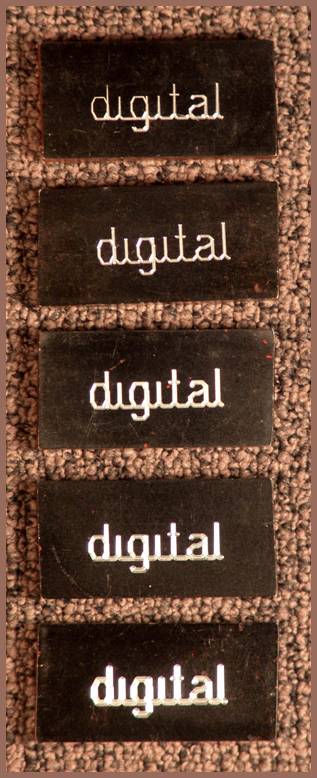

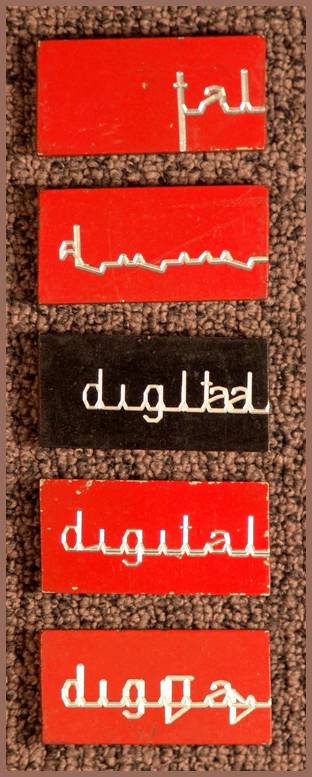

The initial attempt was based on a simple Cartesian representation of the DEC logo that strung together a series of connected straight line segments. The test artifacts were cut on a Bridgeport milling machine out of aluminum blanks.

Progress was made on determining the aesthetics of cutting letters out of painted aluminum. The resolution and form, although still piecewise linear, got better and a good line width emerged. Ultimately, an appreciable facility at milling machine calligraphy was obtained (below). The final system was able to perform circular interpolation (via judicious use of Bresenham’s fixed point digital differential analyzer algorithm) on two of the Bridgeport mills while time-sharing creation of new parts programs with the operator on the ASR-33 teletype.

However, truth be told, there were a few bumps in the road. “Hey, that’s not the hardware’s fault” was heard more than once.

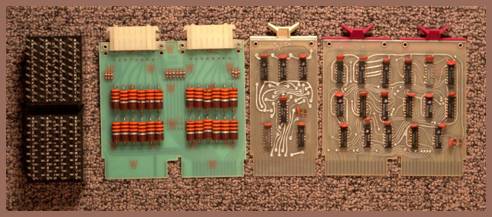

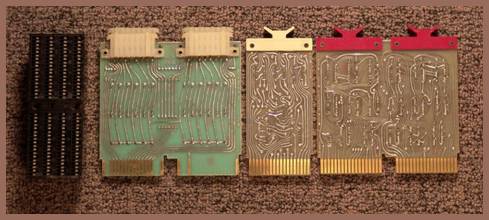

Speaking of the hardware, the first products I designed were two types of switch-tail ring counter modules (M261 and M262) and ballast resistor boards that could accommodate the different types of stepping motor designs. The boards are shown below together with a wirewrap mounting block.

As can be seen from the images below, it wasn’t a time for prototype beauty contests. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to locate color photographs of the finished product (B&W photos can be seen in the 1971 DEC Control Handbook). Try to imagine the DNC ensconced in its NEMA cabinet on the shop floor dressed in the really bright colors seen on the blanks above. Think of the frame below wrapped in a heavy metal cabinet painted bright red and sporting a large black bump-out access door. When the two silk-screened control panels positioned on top of the cabinet had their Nixie tubes flashing and industrial push buttons ready to control it all, it looked like something straight out of Metropolis.

In fairness to DNC, the contemporary prototype for the PDP-11 was an equally unbecoming rack of wirewrapped M-series modules. They were experiencing problems with flexure inducing cracks in the etch and around the plated-through holes in the new quad-height boards. Nonetheless, the ungainly prototype served the maiden PDP-11 Hardware and Software Training Courses (of which I took part) quite well. As with the DNC, function did not require beauty, and Ken Olsen signed each of the training certificates (as he personally still did in those days). Good memories of Russ, Ralph Hamilton (engineer) Dave Westlake (programmer), Lenny Dionne and Gerry Gagnon (the technicians who built the beast), wherever y’all are.